Respecting a mason series with Master mason, Dawood ji.

The real heroes of natural buildings are the ones who have worked extensively, trained themselves and carried forward the traditions of building that their ancestors have taught them. These are experienced hands with knowledge and understanding that come only through sharing an intense relationship with the materials. With the advancement of the industry manufactured homes, very few such gems remain behind. They are the last of their generation with awareness about indigenous buildings methods which are threatened and are a part of the very delicate link that connects us to the past. As they struggle to fit in the modern society began many to deviate and choose to work with synthetic materials. Very few boldly took up family traditions, having faith in what they considered sacred. ‘Respecting a mason’ series was born out of the need to address such people, learn from them and do our bit to revive their knowledge through our practices.

When Dawood ji, a 62-year-old traditional lime mason from Rajasthan who has worked extensively in restoration and traditional building, travelled all the way to Tiruvannamalai to meet natural builder Biju Bhaskar and his family, an inevitable connection was bound to transpire. The relationship established in the process of understanding lime and each other, transformed into a lifelong bond of trust and friendship. Dawood ji’s father Muhammed Ibrahim who is now 97 years old, has four sons and five brothers who are all connected with lime. Truly, working with lime runs in the veins of the Muval household.

To understand this mystical material better with the help of Dawood ji, Biju Bhaskar has been experimenting with using lime for storage tanks, water-resistive finishes, flooring and flat roof. Meticulous and systemized in his work, Dawoodji brings alive the workspace with his quick wit and humour while keeping everyone on their feet. An avid Urdu literature enthusiast, his deep philosophies and shayaris are combined in his teachings of the ways and behaviours of lime. Sharing his stories and encounters in natural buildings, he accompanies Biju Bhaskar to explore the multidimensional, much less understood Ruhani (spiritual) material- lime.

Below is a snippet of the many conversations they shared, presented in Dawoodji’s ada (style) which will help me know a little better about material as dynamic as lime, along with understanding a bit about our lime master Dawoodji.

Tell us about your journey with lime

Whatever I know about lime, I have learned in my village Sardarshahar in Rajasthan. My Grandfather used to cook lime out of limestone, so did my father. I worked as a begari, helper in my village around the age of 16, that’s where my journey began, understanding the ways and behaviours of lime. I understood that the trick lies in mixing, I understood how different uses of lime have different mixes. I got a grasp of that because in my village people extensively worked in lime and they still do. Then I moved on to Jaipur for two years, which eventually brought me to Mumbai. Therewith my uncle, I trained to become a mason. I didn’t get a single penny, but my learning is what was my true earning. I then went to UAE, Muskat and there again I worked as a mason only to return back to Mumbai. One day Vikas Dilawari ji (conservation architect based in Mumabi) found me and gave me the platform to work with lime. I have worked with him for 16 years and now for the past four years, my son Altaf is with him. He gave me the freedom and space to explore lime using the knowledge which I had acquired. For me it was commonplace, I had seen my family and villagers working with lime even as a child. Once the concepts of lime are clear you can devise ways to work around it. Since then I worked on all kinds of conservation projects in Mumbai and my knowledge of lime from my village was applied in the conservation of heritage buildings. I worked with the restoration of Bhau da ji lad Museum, Rajabai tower and Elephanta caves to just mention a few. These heritage structures were in pathetic conditions, dilapidated and ignored because no one knew how to bring them back to life. I successfully managed to restore these in their original form using lime. I was also acknowledged for my work and have received 6 awards until now one of which was presented by Ratan Tata for my work in restoration. I am here now because I decided to take a leap of faith and travel all the way in a 50 hours train journey to a far off land and meet and work with people I have never met before, to a place I never knew existed called Tiruvannamalai.

Lime or cement?

I have worked with both, and I find it easier to work with lime. Lime involves a lot of processes and people don’t have that kind of time now. We want homes to be ready quickly, so the next day madam can walk on it or take a shower as soon as the bathroom is ready. But to tell you the truth, lime understands the weather and responds accordingly. During summers it will keep you cool and during winters it will keep you warm. It is definitely more time consuming and meticulous than cement, but also more rewarding. One thing with cement is that you always need steel to work with it, with lime you don’t need steel. In 20-40 years, cement will swell and fail, it is bound to happen sooner or later because it has a limited life. Cement is hard, but lime is soft and gentle. When you try to break it, apply force intentionally, it will obviously break. But leave lime alone, don’t disturb and it’ll serve you forever. On my sites, engineers come with hammers the next day and say that the lime isn’t strong enough, without really understanding lime. What to tell, such fools!

What are the different types of lime and what are their specialities?

This is what I know about lime and is specific to the place where I come from, I do not know if things are different around here. There are two different types: one is chuna the other is kali, depending on the topographic location where they are found. Chuna is made by baking as the stone which is called kachha dagad and is found on the plains. When the stone is from the mountains, burning it in a kiln will give you kali. The difference between kali and chuna is that kali is pure bright white while chuna is off white.

Kali is far richer than chuna and this ‘Chinkni’, lubricious kali will crack more. Hence more quantity of surkhi needs to be added to kali. This creamy and luscious kali is used in superior finishes of walls and for whitewashes. Chuna will require a lesser quantity of surkhi to be added and used for rougher works.

Tell us more about surkhi and the admixtures added to it?

Powdered burnt clay is called surkhi, it may be made using burnt bricks, burnt clay tiles or simply prepared by burning the right kind of clayey soil. Surkhi is what makes lime into ‘lime’. Without surkhi, lime is only good for limewash. Lime and surkhi come together to make a homogeneous mix. Jaggery and fenugreek seed water is added to this mostly when doing roofs or repairing cracks. Jaggery is sticky, enhances binding and keeps moisture intact preventing sudden drying and hence preventing cracks. Methi gives workability and adds to the waterproofing quality of the surkhi mix. In a mortar, the jaggery holds two bricks together tightly. For plaster, it is unnecessary to add jaggery. If you add it to the plaster, the consistency will change and will not give the desired result the mix will become and lose and take longer to set.

What fibres are added to lime plasters and what is the function of those fibres?

Munj fibres (Saccharum munja) and jute are the fibres commonly used in lime construction. There is a difference between munj and jute. Munj is made with dry grass found in wetlands, the same one that they use to make a charpoy, and jute is the one that they make jute bags with.

Munj fibres are used in the plaster mixes after finely chopping them. It gives tensile strength, gives a firm grip to the plaster to hold it together tightly. These fibres prevent cracking, even if it cracks (which is the inherent nature of lime to crack and self-heal), the cracks will be connected by these strands preventing deeper cracks.

Jute rope is placed in horizontal and vertical planes between a thicker layer of floor to make a grid or strips of fibres. After the brickbat is laid, we lay a layer of lime-surkhi above that. Then strips of jute are laid in a grid-like pattern and again covered with a layer of lime-surkhi. This natural way is a simple way of lime reinforcement and works fantastically well. They use and steel and cement concrete we use jute and lime surkhi.

What is your view on plasters for a base made up of earth, what kind of plasters would be preferred?

Everything is about connecting the plaster with the base, you cannot apply a stronger material over a weaker base, this will tear it down. For softer walls, use gentler and softer materials, for stronger walls use some tougher materials. Lime is fire ‘aag’, violent and ferocious, the earth is ‘mitti’ gentle and calm. Fire will tear the earth, so applying the strong lime over the weaker earth base may not be the best idea, however, you can mix lime to mud to make it blend better with the base when you coat over earthen walls. Also, cement plasters are a big NO, because they are a lot stronger and will not work with softer earth walls. Understating this basic principle is very important when dealing with lime which comes with no recipe.

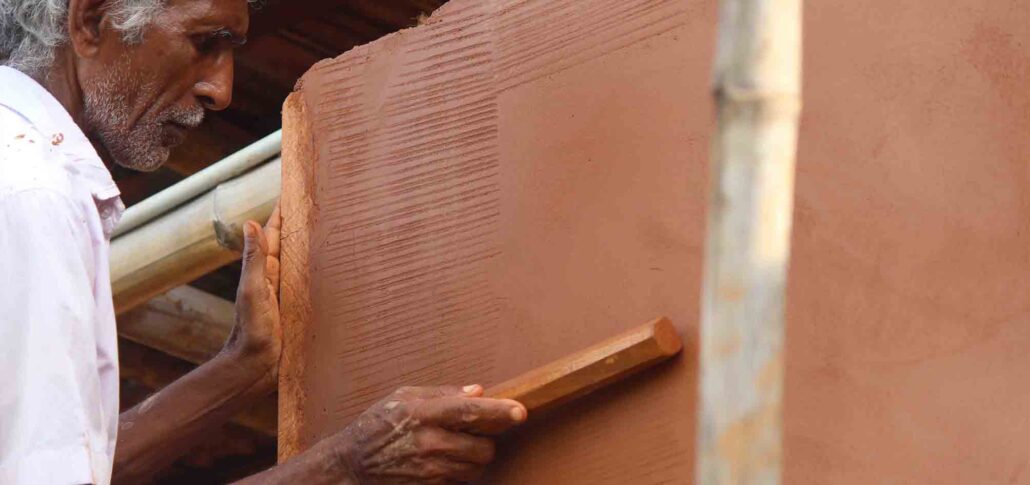

What is thappi and why do we need to do it over surkhi?

Thappi is a term used in Rajasthan, I do not what they call it in other parts. It is the process of gently tapping the surface when the process of hardening has started. Without thappi, the practice of lime-surkhi is incomplete. It will not have enough strength to hold itself, it will be loose and will be prone to more cracking. It is also a process of binding and ingraining the layer of the plaster to the base layer.

As soon as the coat of plaster or roof is done with surkhi, it is lightly tamped with a wooded piece. Then as it becomes dry, the intensity of tamping is gradually increasing till you hear a ringing sound. The first tapping makes sure that the coat sticks well to the wall or the substrate and sets well with it. It also prevents cracking and gives strength to surkhi. This is the most important step that cannot be ignored. I have seen that my fellow villagers always do this with lime works.

What about using sand with lime?

Sand is used in cement, and as a combination works well with cement. The same is not true for lime, it cannot bind with sand. The strength of the resulting mix will not be sufficient and it may crumble because the mix is not homogenous. There is no mel (union) between lime and sand. With surkhi, lime becomes one, but with sand, the particles of the materials are still separate from each other after mixing. Surkhi also helps with its absorption properties, to set and create a stronger bond. Sand is more of an inert material like a filler, whereas surkhi has a relationship with lime there is a connection, hence I feel lime and Surkhi are better partners, more compatible.

How do we make a lime wash and what is the importance of a good limewash?

Mix lime in water to get a sufficient consistency, watery just like paint so it can be easily applied using a brush. For old walls you need to make a thicker mix, for new walls make it more diluted because fresh walls will absorb more water, 3-4 coats should be good to go. Limewash makes a lot of difference in the water-resistive properties of the wall. It is a surakshakavach (safety shield) for the plaster. There is no measurement in preparation of mixes with lime, only intuition.

Salt is added to the whitewash, this greatly reduces the dusting of the whitewash. A little neel, that is used for washing clothes (in powder form) is tied in a cloth and stirred with a stick in the mix. This makes the colour bright, and the wall will look as good as new, even after 2-3 years. Before any function in the house, the boys of the house get some lime and neel and paint the home. These whitewashed walls are safed sada bahar, our lime is very seedhi sadhi (simple), just like our villagers.

You are an admirer of words, in what ways would you connect your passion for literature and songs with lime?

Shayaris are of great meaning to me, written by people who are unconcerned by worldly matters. These people who have reached another level of consciousness and their works have always captured my attention. As a child, my father was the one who introduced me to this altogether different world of books and words. I used to sit glued to radio programs with gazals and shayaris when I was a kid and my passion for this only grew. I may be uneducated, but I know the value of books and words.

The work I am involved in is quite different, in our field have you seen people talk to each other? Their language is raw and rough. This laborious work is for people who have no other means to fend for themselves. After a hard day’s work coming back home with soiled clothes all one needs is a cool shower and a good nap. Do you think they have a care for this shayari and songs? What good is a poem here? I do not connect my passion for words with work, they are different things. Masons and shayaris? These two are the least connected, yet it has fed my soul and kept me sane all these years.

What lies ahead in the future for you? Do you think there is a revival in natural building happening with Thannal?

In the future, I will be working with Biju ji and I also plan to work in my village.

About revival, I am going, to be honest, that I cannot give a one-sided answer. I haven’t reached a conclusion yet, I’m in a deep dilemma. One side is this where Thannal is working in the building using traditional techniques and the other in the market (conventional building industry) with their tall structures. I cannot say what is right, I am very indecisive right now. For a place with higher density let them make their high rises I wouldn’t say that they are wrong. But what Biju ji is doing I feel has started something in the villages and is going to surely prevail. This is a very good solution for people who cannot afford homes and I can see that people are taking heed. I believe this will be very successful in this village and will change the immediate surroundings, people around here will start having more natural buildings looking at what we are doing. Yeh ek rivayat Ka agaaz hai– this is the start of something legendary. The work that Thannal is doing is basically conservation, conservation of the ways and methods of our past. This is the rebirth ‘Punarjanam’ of mud. We had ignored it for a long time now, we had thrown it discarded it, and had forgotten how to do it. Now people are understanding its value and this effort at revival is bringing about a change, or rather has started a change. This process is bringing it back to life once which was dead it is indeed a new life of earth in buildings.

Before coming here I had a completely different idea about mud building and now I have started learning with Biju ji about the beauty of working with mud and there is much I still have to learn. I have a diary I make notes of every day, they have the delicious recipes of mud. I am a teacher here, but I am also a student learning with Biju ji.

What do spaces mean to you? Do they have a quality, a certain spiritual aspect to them?

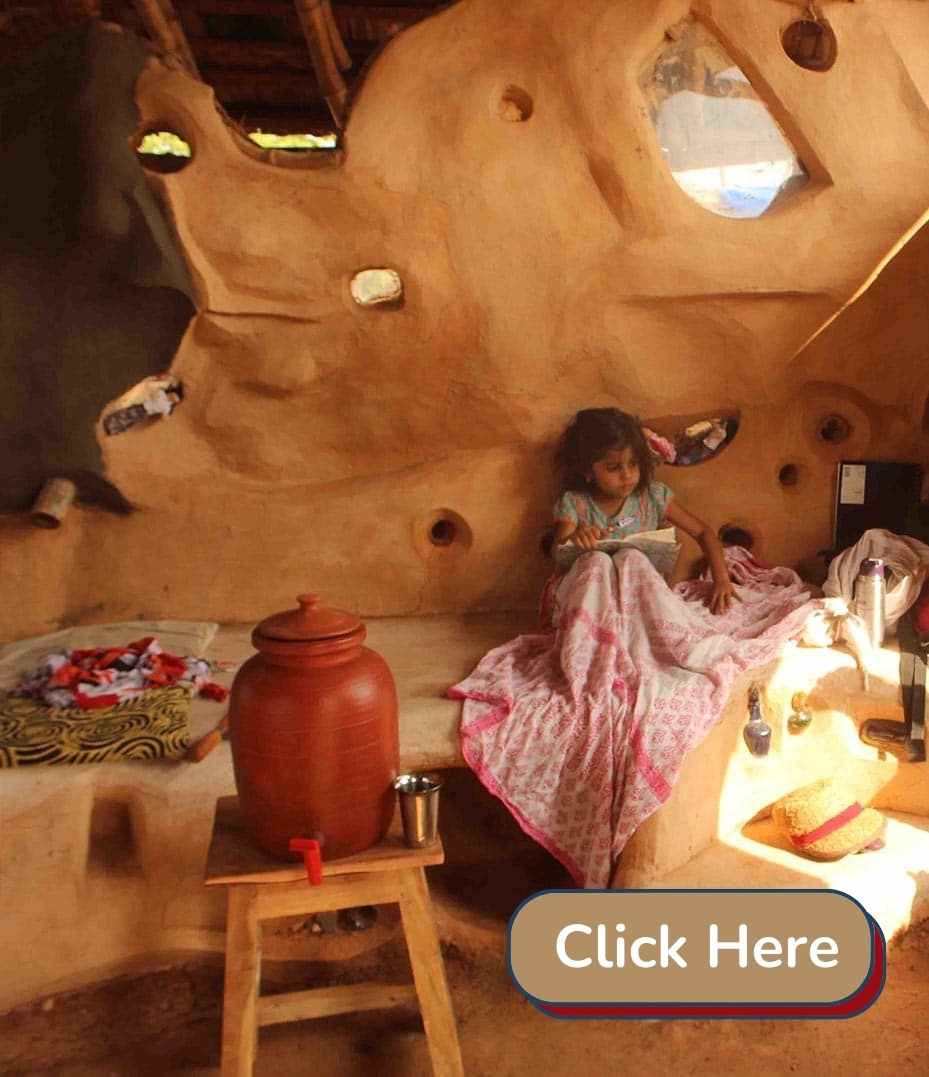

Yes, spaces do have a spiritual essence to them. And it is true for mud buildings which have a direct connection with your mind, body and soul. It is how the space makes you feel, the comfort it gives you physically and spiritually. Where your body and mind are both at peace. In the olden days, they just left the jharokhas open to let in the fresh air and you could peacefully sleep without a care. Nowadays homes are always suffocating even with their Ac’s on.

Do you see the link between the earth and us? We are connected for many births. After one dies, they recite an ayat from the Quran before they bury the body, they mention mud in it. It means that we created you from the earth and we shall return you back to it. Indeed, that is what we are made of and at some level, all of us inherently feel the connection that we may be unaware of.

How was your experience with Thanal for a year now?

I would re-frame this question to ‘what did you experience, what did you imbibe in yourself through this journey?’ I have had lots of different experiences, but this was like no other experience. Everything was new, the people, the place, the language, but I had the most beautiful experiences here. I have never worked with these kinds of people who became like a family to me. The system of working is so different.

We had built this water tank here using bricks and lime mortar I had not imagined it would work so perfectly. My faith is renewed in adobe, you can see that not a single drop of water leaks, this experiment was a huge success.

I tried my hand in mud building, learning and enjoying the process, understanding the technicalities. I was a little apprehensive before but now I wholeheartedly want to study more about building with mud. I have started to write about it as well. I may not be here tomorrow, but this diary will. Maybe someday it will help someone. On a parting note, I share this shayari:

Rondhi aur kuchli hui aarzu bhi rang lati hai,

besabab samajhke phenke hui mitti bhi mina ban jati hai.

Musharaff Hebballi

This article is by Natural builder Musharaff Hebballi. This post is part of our People & Interviews series,.

3 thoughts on “Understanding lime with a sprinkle of shayari (poem)”

I spent a lot of time to find something such as this

Thanks Amit ji. Surly please keep in touch. April – May 2018 we will be in Sardarshahar, Rajasthan

Thannal is doing a great service to the society by promoting our traditional way of construction. Thanks for sharing some great life time valuable experiences with us. I would like to make a traditional Rajasthani house with courtyard using mainly stones, bricks, iron, gunmetal, wood and lime mortar. I will be touch for your help. Shri Dawood ji comes very close to my maternal home Churu, Rajasthan.