Table Of Contents

- Introduction

- Methods of natural building

- Planning

- Structure and materials

- Conclusion

Ganjam village near Mysore is still reminiscent of an old village with exposed mud and groups of people gathering around for casual conversations. One of these houses that were well kept and striking in the village was this 300-year-old house is still inhabited and well maintained till date as a gift of earth from the ancestors. Owned by G. M Puttilingaya and Laxmi akka, this house still retains most of its ancient history except for a small new extension for a storeroom and the replacement of mud and cow dung floor by oxide and tiles. Back in the time, there were no architects or contractors for building a village home, it was almost always a family/ community affair. This house was constructed by Mr Puttilingaya’s grandfather along with his sisters. They worked as farmers on their farms. In Ganjam village, many traditional houses are still retained, but also many are being replaced by very easily obtainable cement. Most homes are in dilapidated conditions, or not cared too much for. They give a hint of the way these houses must have been constructed. The family inhabiting this house is small, and the house now seems too big. Initially, where many families used to live as a joint unit, everyone has now moved to the towns and cities in search of better ‘prospects’.

During the times the house was built, the village was self-sustainable. All their needs were met within the village itself, except for salt and clothes, which they bought from nearby towns and villages. Different communities were involved in different crafts and trades that were specific to their community. For example, kumbhars, potters specialised in making clay pots and pans, vishwakarmas were carpenters who developed advanced carpentry skills and woodwork. The entire village thrived on the barter system as most villages did in India at that time. Not relying on the external economy, they had their own local economy which was based on the exchange of goods for services and vice versa. All this subsided after independence, and thus began a change in the economy, to standardise the mode of exchange.

The process of building was purely local. The clay tiles, lime, wood, mud, cow-dung, etc. were obtained from the village, so were the skills of the masons and carpenters. Every profession was seasonal, even construction. For example, the current in the river used to bring the sand on the banks when the rains stopped. So that it could be utilised for construction. Respecting the flow of nature, everything human intervention was harmonious with nature. We waited, slow and patient for nature to guide us. The slow life was harmonious with the laws of nature.

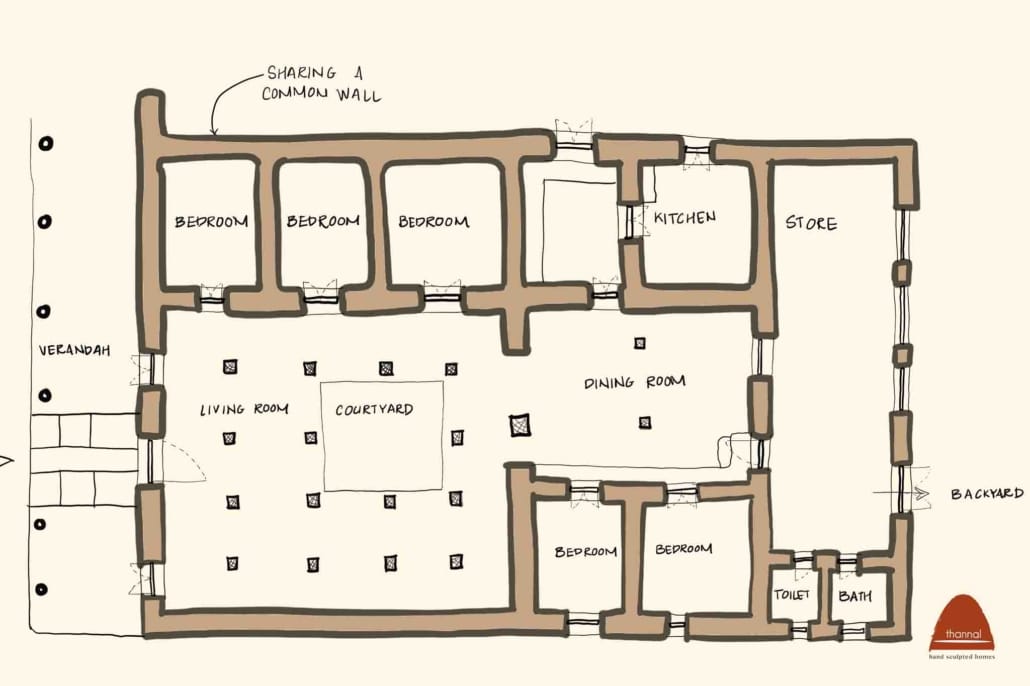

This house shares a common wall with a neighbouring house that is built in a similar fashion. The houses here follow a language, giving a more cohesive look and feel to the streetscape.

Methods of natural building:

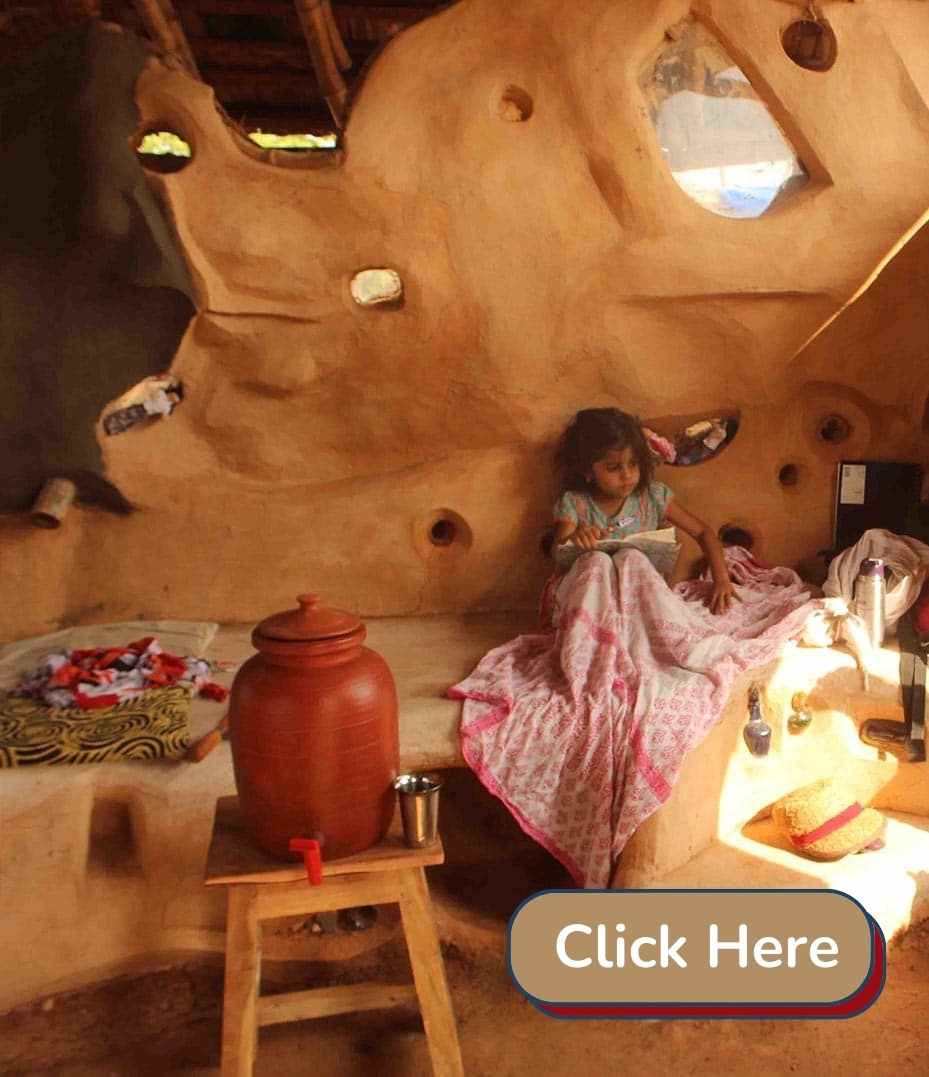

What is unique about this village is that the houses here are wattle and (daub) cob houses with tapering walls. The wattle structure is daubed with generous thick cob and these then become thinner as we go to the top. Generally, most systems of walling are either wattle and daub or cob, a combination of both is rare and Ganjam village displays these unique typologies of buildings. A great advantage of this in the modern context could be that the structure can be constructed first to have the roof erected. Work on the infill/ walling can then continue any time of the year. This gives great flexibility to working in unfavourable weather conditions. The ridge has pieces of big pots to protect the roof. Here is an example of a farmer’s home, a part of the Thannals project that follows a similar pattern of building.

Do you want to study Natural Building Online ?

Planning:

The plan gives a clear idea of the layout of the house. The entrance verandah is a large enough space for an informal meeting, evening chats with neighbours or a quiet lazy afternoon nap. The cool and shaded verandah is a great transition space that leads you inside the house. The entrance unveils a huge common space that includes an open courtyard. The courtyard was used to dry foodstuffs in the house. The colonnade breaks the long spans and supports the structure of the roof. This common space leads to three bedrooms and the dining hall. The dining hall again leads to two rooms and a kitchen that was later split into two. A brick-wall extension was later added as a store-room and toilet and bathroom. The backyard has space for cattle.

The planning of houses in the village largely depended on the community it belonged to, and the occupation they were engaged in. The verandah was one constant, only the size of it kept varying. Since it was majorly an agrarian community, and had animals they depended on, houses had the back portion for their useful animal friends.

Structure and materials:

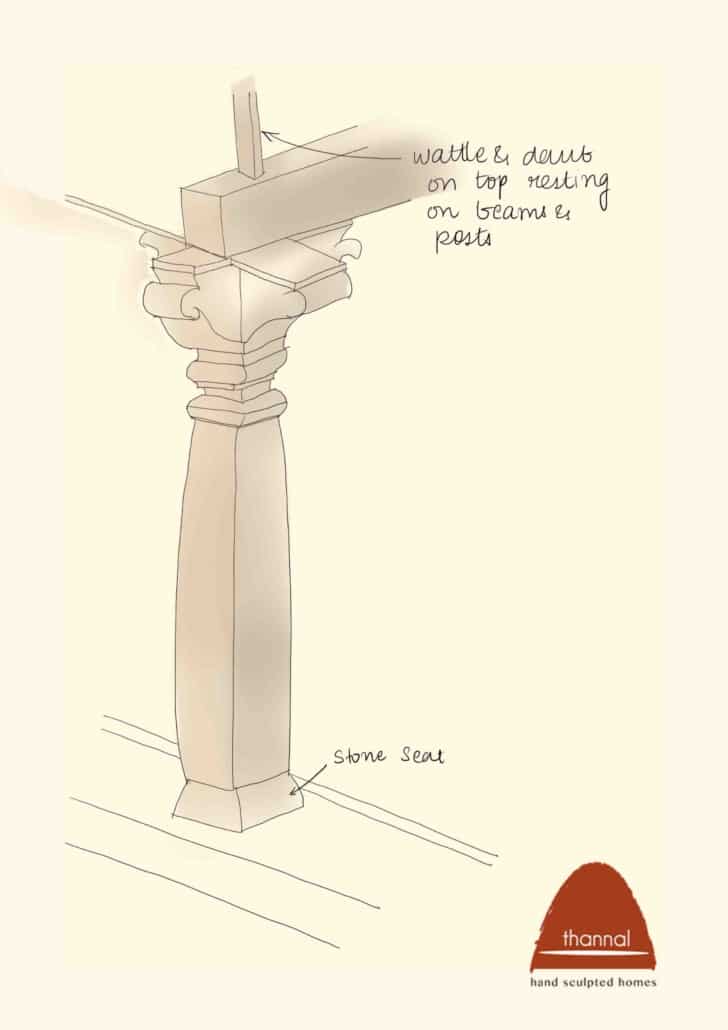

This is a composite house, and has a wooden post beam system for the large spans, while the bamboo frame inside the thick mud walls comprises the enclosure of the house. The mud walls evidently taper towards the bottom, a sensible way of wall construction for proper load distribution and also for saving material. Above the beams, the walls are thinly made with wattle and daub. The roof is supported on columns and load-bearing walls, while the truss takes care of the large span. The truss made from teak wood is an interesting structural design feature and perfectly takes care of the roof load. The country tiles used for the roof were traditionally the local handmade tiles that were kept on bamboo splits to make the interiors cool. The sketch explains the detail of the structure of the post-beam and truss.

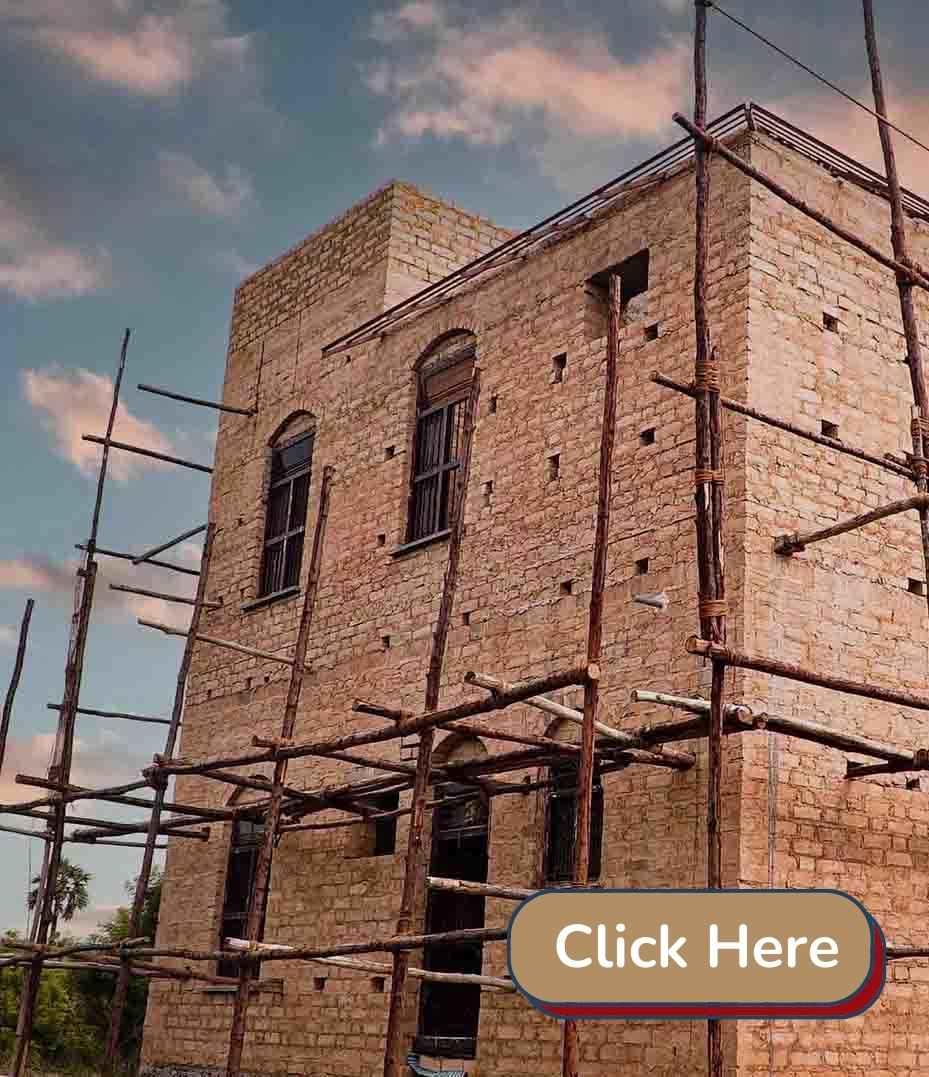

The mud that was used for building was kept wet for a few days to rot. This made the mud sticky making it very hard on drying and soft mud transformed into a very strong wall. The outer face of the wall have stones faced to protect from the weathering elements, a simple reminder to shield the mud walls from the rains, and the house will last for a very long time. The natural shaped wooden beams and rafters are a design statement, aesthetically pleasing, they question the need for perfectly cut square/ rectangular sections that are used in design nowadays with the availability of power tools.

This house has extremely well-regulated temperatures, due to the thick walls and the courtyard that is the special feature of the house. The courtyard invites the sun, rains and gentle breeze into the house. These elements purify the house and add to its beauty. The house has partial attic spaces for storage and drying food grains.

Unfortunately, just a couple of days before this house was being documented a 90-year-old mason passed away. This comes as a blow to how much information about the house is lost, as no one around really knows about the details of the construction process. This is a reminder to us all, that time is of critical importance and we need to connect with craftsmen, and artisans about their skills, because maybe with them, this knowledge will be lost forever. And people like Lakshmi akka and Mr Puttilingaya, heirs of these heritages preserving their roots are the people we need to cherish.

We thank Mr Balachandran for graciously helping in making this possible, and Maitree for helping with translation. We are very grateful for Prof. Karimuddin, an 80-year-old resident who imparted his invaluable wisdom to us.

Biju Bhaskar & Musharaff Hebballi

This article is by Natural builder Biju Bhaskar & Musharaff Hebballi. This post is part of our Ageless village series,.