Speaking Natural Finishes – series 5

“Your skin is the reflection of one’s inner health”

The people of Wayanad have taken this very literally for their humble abodes of adobes; anagram anyone?

The traditional plastering techniques of this region are based on their locally available resources as a natural finish should be. That is the first rule of the vernacular. A natural finish, whether plaster or an earth-smeared floor is always energy efficient. The materials for which are non-laborious to collect, easily sourced. These certainly react well with the climate; keeping in mind that they are born of the same.

Wayanad is a host to a beautiful earthen finish in the palette of earthen colours. Stunning rich greys, pearly whites and deep blacks. All represent the five elements of nature perfectly.

Why a need for plaster if one may ask?

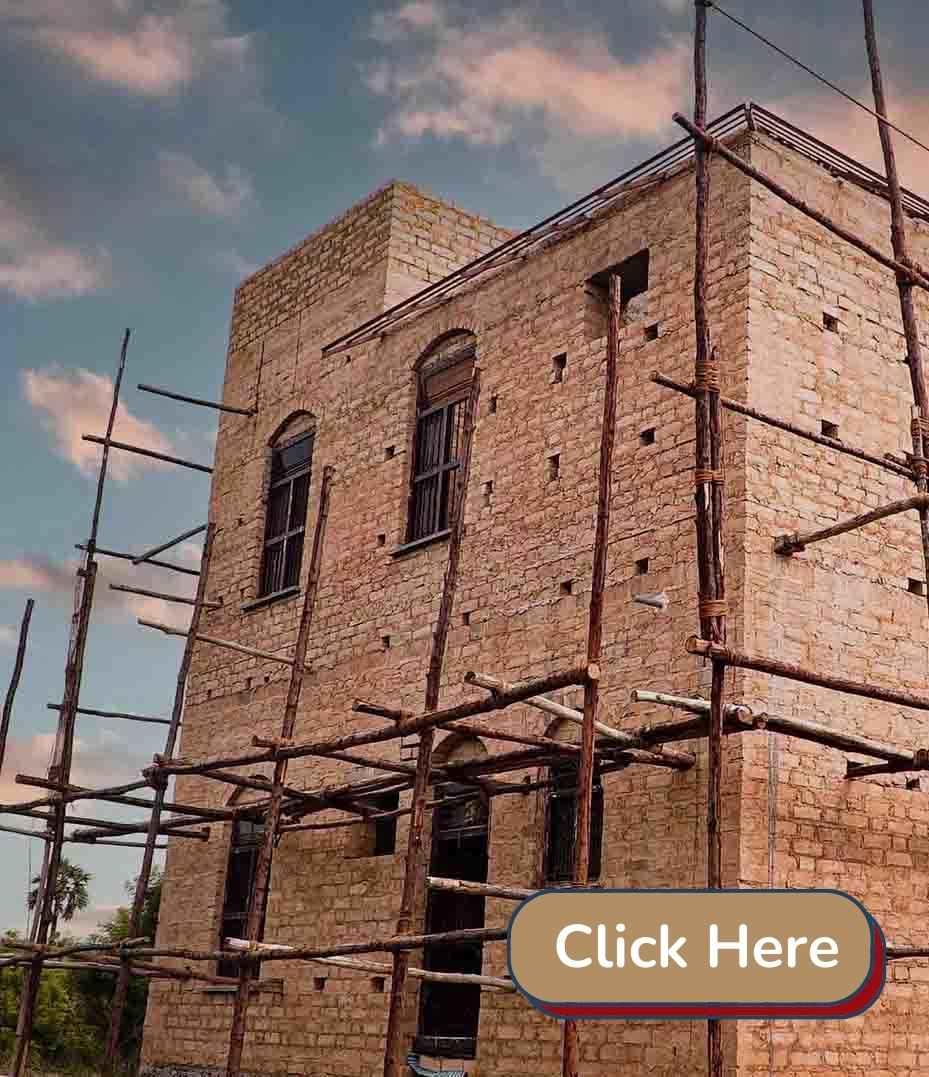

With the material that is used to build their homes, usually plastering is essential. A good earthen finish will protect what’s underneath, mud blocks, mud monoliths (cob), rammed earth and all!

In a land of abundance as this, there are myriad of materials to choose from. Most ingredients are farm-based, cow dung

& Rice husk is one of the most easily available!

The Pearly Whites

The rich white plasters are often used for walls, ideally to reflect the glare from the sun and the heat as well. Ramaettan’s home is a brilliant example of glowing finishes. The plaster which coats this home is simply the white mud found in the beds of the nearby streams, or at the bottom of the ponds. This mud is basically clay; the process used to make these plasters is interesting indeed. The geology plays a vital role in determining the colour palette for the earthen finishes here.

Ramaettan mentions how this white mud is collected from the sources first; though this isn’t used directly for plastering. Pots are made with this mud (which is really clay). The reason may be that the time the mud is collected (post-monsoon) won’t coincide with the season of plastering. Thus these pots are made and stored, uncooked. The walls have to be plastered before the monsoon arrives. It is then that these mud vessels are broken and used for plastering the house.

Talk of wall finishes and leave behind Lime; certainly not!

Kummayam which lime is locally known as is a chief ingredient for these water resistant finishes here. The lime used for plastering is usually Shell lime. Shell lime is the purest form of lime, what it lacks in strength compensates with its ability to resist weathering!

The other white plaster is generally the ultimate most coat, a more protective one. It combines lime, fine river sand & the bark extract of a tree known as kulamavu. The lime offers water & pest-resistant properties. The fine sand binds and gives strength, while the bark extract offers anti-fungal, anti-bacterial properties.

What is Kulamavu?

A tree native to this region, Kulamavu is a recurring ingredient in the homes of Wayanad’s hamlets. It is actually the extract from the bark of this tree is that is used while mixing plasters and floor finishes. Scientifically known as Persea Macrantha, the extract from the bark is known for its phenolic contents, that lend it its anti-fungal, anti-bacterial properties.

Apart from being used as a chief ingredient in earthen coats, the sap is also mixed into the mud which is used to build with.

Since the soil of Wayanad is so potent, it fosters and hosts a lot of microbial activity, which no doubt in nature keeps the cycle running. Some microbes in our building are bad news, which only illustrates why Kulamavu is an excellent addition to the rich earthen plasters & floor surfaces.

Do you want to study Natural Building Online ?

The Greys

The greys are the most often found in this land of plenty.

Ramaettan’s home portrays earthen finishes of greys and whites. The ash from burnt rice straw contributes to the deep grey. When burnt the cellulose of the rice straw reduces to silica. The ash is also a very good candidate for thermal insulation. The other ingredient used is the sap from the bark of the kulamavu tree. This sap and the rice straw ash are combined to make a fine plaster. This is then applied as a final coat over dwellings.

These plaster do not limit themselves to a plain opaque coat but it also becomes a medium of expression. When the grey mixture of ash and kulamavu sap is wet, interesting patterns are created on these walls; created by swift movements of the fingertips.

The patterns have a glossy appearance and bring out another shade that contributes to the aesthetics of the building.

Art on the wall! Traditional patterns are drawn onto the walls with fingertips, while the final layer of plaster is still moist.

Touch walls, before touch screens were introduced.

The red of the plinth compliments the grey patterned wall, for this shaggy roofed home.

The local soils used to bring out beautiful colours on the walls.

Floored.

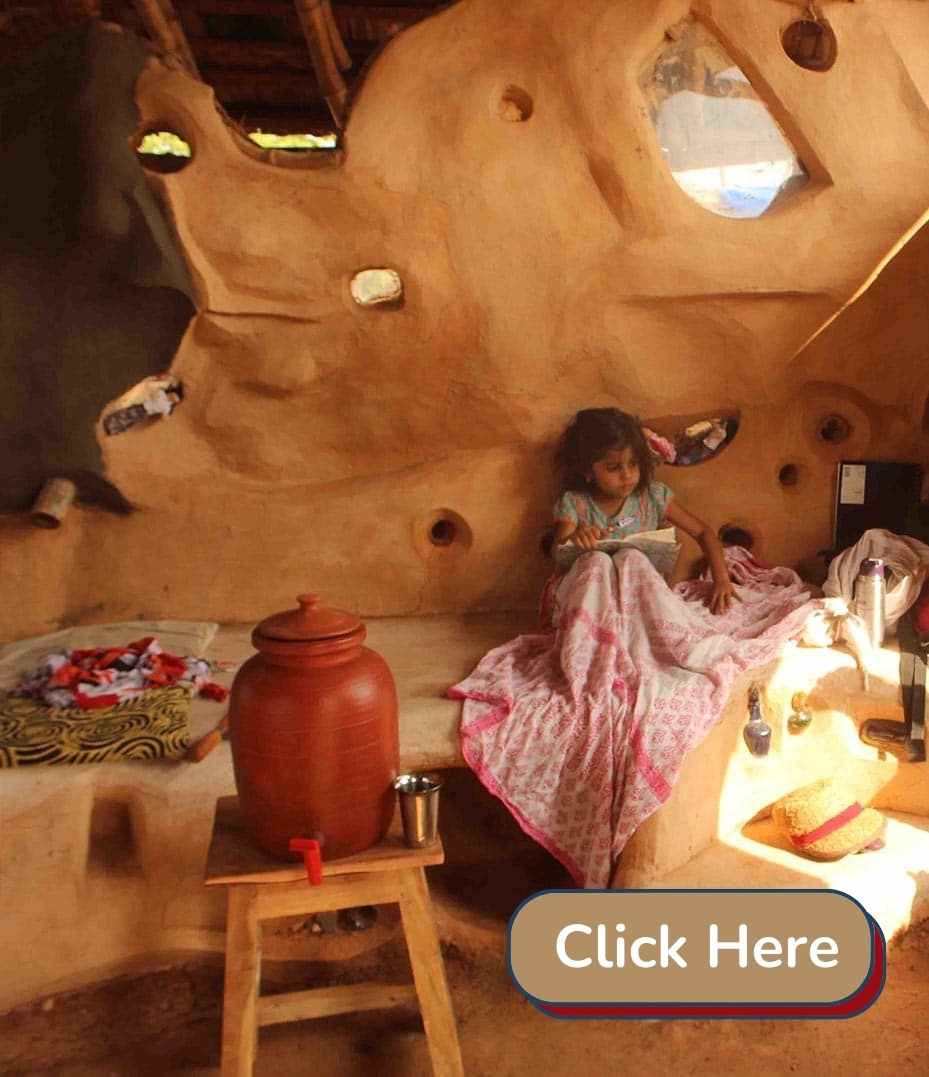

Yet another black greys that comfort your senses, we find Ramakrishnanji’s floors and seating spaces smeared with a black grey of cow dung and ash, which they have proudly named the Japan Black Finish.

A rich grey that provided a comfort for the foot, one of the main source of body heat loss, provided an insulated surface that were warm during the winters but cool during the hot summers of Wayanad. The veranda, the seating there upon the living rooms, kitchens and all these small spaces were cleanly finished with a coat of the rich grey mix. Even the Chulha was carefully lined with the same.

Ramakrishnanjis’s wife explains the process for making the Japan black floor finish with great care as she is the one who so lovingly prepares and applies the coat every few weeks. “The floor has to be fixed first as it has an undulating texture. For this we mix mud, rice husk and a little bit of sand is also used. We apply it with our hands.” She speaks the excitedly.

“After the first coat has set we prepare the second coat with cow dung, mud and a sap from the plant known as kulamavu (read more about it here).” The third and the penultimate coat consists of cow dung only which is a pest resisting ingredient; this is the setting base for the final coat. The chemistry of the cow’s stomach certainly contributes to this beautiful floor, but more so when the cow dung comes from a traditional Indian cow breed.

The final coat is what the cool grey warmth is all about. It is a rich combination of cow dung and ash with water. The ash is often the charred residue of burnt straw. Although lampblack is also used as it gives a jet black pigment.

Above images

Rich grey warmth. No off-gassing here!

Ramakrishnanji’s wife, applying the final coat which is a blend of rice straw ash and cow dung mixed with water to make a thin paint.

The warm grey floors at Ramaettan’s home, where each surface becomes a medium of expression.

This final coat is like the skin on our body it needs renewal periodically, every few weeks. The first application of this final coat however needs a good quantity of cow dung. This is applied with hand and is a thicker layer. The remaining application, after the previous layer s dry-wet, is done by cloth. This mixture has more of a watery consistency which is why cloth application is opted..

These earthen finishes of Wayanad are a result of a thorough research by our ancestors, that throw some light on insightful facts. It is now with the crutches of modern science that we can understand how inhaling cow dung smeared floor is equal to taking an anti-depressant. How carefully orchestrated the natural farm produce is, for the rice straw ash to be used to coat our floors. Sometimes the answers are just around the corner, material in our backyards waiting to be explored. And all we have to do is get plastered!

Biju Bhaskar, Musharaff Hebballi & Anushree Tendulkar

This article is by Natural builders Biju Bhaskar, Musharaff Hebballi & Anushree Tendulkar. This post is part of our Natural Finishes series,.